By: Noor Johnson, Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado Boulder; Mary Beth Jäger, Research Analyst, Native Nations Institute, Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at the University of Arizona; Lydia Jennings, PhD Candidate, Department of Soil, Water, and Environmental Science, University of Arizona; Amy Juan, Sovereign Remedies, LLC; Stephanie Russo Carroll, Assistant Research Professor, Native Nations Institute, Udall Center for Public Policy and Assistant Professor, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona; and Daniel B. Ferguson, Associate Research Scientist, Institute of the Environment, University of Arizona.

On a sunny morning in June of 2019, our hosts at the Athabaskan Nay'dini'aa Na'Kayax' Culture Camp, located near Chickaloon Native Village in south-central Alaska, set up a table near the smoke house and demonstrated how to fillet salmon. It was salmon season in Chickaloon, and young campers were learning how to process fish: how to fillet, smoke, and preserve it in oil. First, children and youth from the camp were given the chance to practice their knife skills, with adults standing behind them and offering encouragement and gentle correction of technique when it was needed. Adults also taught the children Ahtna words (Ahtna is part of the Athabaskan language group) and stories as they prepared the salmon. After the children had all had a turn, camp leaders offered our group of visitors the chance to try. Amy Juan, a member of the Tohono O'odham Nation (located within the Sonoran Desert in south central Arizona) , eagerly stepped forward. "I've always wanted to learn how to fillet fish!" she said, explaining that since she came from a desert people, she had never had the chance to try. (See Photo 1.)

This was a unique opportunity not only for Amy, but for all 15 members of the Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network (IFKN) (plus two spouses and four kids) who were able to participate in the culture camp, which teaches language and important cultural skills and knowledge to children from Nay'dini'aa Na'Kayax'. The camp was started by the community to create a space to proactively share language and cultural knowledge in which children could learn from elders and knowledgeable adults. This was the first time the annual camp was opened to a group from outside of the community

IFKN is a four-year (2017 - 2021) National Science Foundation funded Research Coordination Network (RCN) that brings together Indigenous scholars, practitioners, and community members and non-Indigenous scholars to exchange knowledge and experience in support of food sovereignty. So far, these gatherings have been hosted by the Gila River Indian Community Department of Environmental Quality near Phoenix, Arizona in March, 2018; Sustainable Nations, a community organization located on the Tohono O'odham Nation southwest of Tucson, Arizona and straddling the border of Mexico in March, 2019; and Nay'dini'aa Na'Kayax, north of Anchorage, Alaska in June, 2019. A delegation from IFKN also visited Sámi lands in northern Finland before participating in the Festival of Northern Fishing Traditions in September 2018. Upcoming meetings are being planned to be hosted by the Hopi Foundation in northern Arizona in August of 2020 and Ukpeaġvik Iñupiat Corporation (UIC) Science in Utqiagvik on the North Slope of Alaska in 2021. More information is available on the IFKN Meetings and Events webpage.

At our first meeting, recognizing the importance of establishing a foundation to guide our work together, we developed an IFKN Network Charter with principles and goals for working with and supporting Indigenous community efforts on food and knowledge sovereignty. Subsequently, we reflected on the importance of establishing relationships with the places that we visit by spending time on the land, identifying this as an important methodology for building shared understanding and accountability within our network (Jäger et al. 2019). We also reflected on the significance of storytelling in transmitting knowledge within and between communities; this has been identified as an area of interest for future work together (Jäger et al. 2019). These and other IFKN principles and goals have helped us create shared understandings and respect, creating a solid foundation for future collaborations.

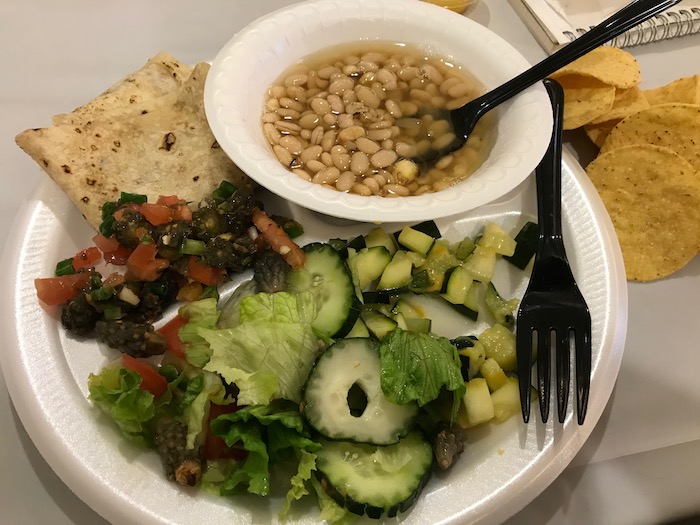

Network members, who include Indigenous leaders, scholars, practitioners, and non-Indigenous scholars, are invited to annual gatherings hosted by Indigenous community-based organizations, and connect between in-person meetings through webinars, listservs, and at related meetings. Network gatherings include visits to community projects focusing on strengthening and revitalizing traditional foods and the lands and waters that sustain them, and innovating new ways of cultivating or harvesting healthy foods. We hear from leaders from the host community involved with projects related to food security and sovereignty, climate change adaptation, and community-based research. And, we visit and learn about important historic, cultural, and spiritual sites (only with permission from the site guardians). Along the way, participants exchange knowledge of plants, animals, harvesting and cultivation techniques, and—a point of significant commonality between the two regions—tensions and challenges they have faced in dealing with the impact of colonial and bureaucratic policies on local and Indigenous food sovereignty. Finally, we enjoy wonderful, locally grown or harvested foods prepared by local restaurants, caterers, and hosts.

While the emphasis of the network has been on learning from programs and initiatives offering concrete solutions and innovations that help overcome challenges to food sovereignty, the group has also spent time thinking together about network practices around research and knowledge sharing in Indigenous communities and with outside entities. Conversations have included talking about the wrongs outside researchers have caused and ways to strengthen relational accountability between Indigenous communities and outside entities like universities. The group has also thought about how to cultivate relationships between people and places that are very different from each other.

After the first two years, IFKN has demonstrated importance and possibilities when Indigenous Peoples and their knowledges are centered. This centering has allowed IFKN to grow and create relational accountability among a diverse group of people and generations from the Arctic and U.S. Southwest. Sharing land-based knowledge of our communities helps inspire current and future generations, awakening us to what is possible. This is best exemplified by an experience we shared while at the Nay'dini'aa Na'Kayax' camp, as Amy Juan of the Tohono O'odham Nation shared how her community members were preparing to harvest saguaro fruit. She described the saguaro cactus, and the sweet fruit they produce, then used a stick to demonstrate how they are harvested, pointing her stick up towards the sky. While talking, she paused to look at the youth who were curiously following her stick, and laughed. "You all are making the same expression we do, while waiting to catch them fall," she teased, continuing on with her story. Upon finishing her story with a song, students' hands shot up to ask questions about the saguaro cactuses, how the fruit are used traditionally, and what the Sonoran Desert is like. It is in these moments of sharing space, stories, and knowledge, that we know the connections we make in these meetings extend far beyond our immediate network. We are excited to see what possibilities the next two years will bring as these relationships grow and deepen.

About the Authors

Noor Johnson, IFKN Principal Investigator, is a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she co-leads the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA). Trained as a cultural anthropologist, Noor has done research on issues related to climate change, community-based monitoring, and Indigenous governance in northern Canada.

Noor Johnson, IFKN Principal Investigator, is a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she co-leads the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA). Trained as a cultural anthropologist, Noor has done research on issues related to climate change, community-based monitoring, and Indigenous governance in northern Canada.

Mary Beth Jäger (Citizen Potawatomi) is a research analyst for the Native Nations Institute (NNI) at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at the University of Arizona. Mary Beth's work at the UA's NNI expands across a diverse range of indigenous governance areas. Some of those areas include child welfare, tribal justice systems, citizen entrepreneurship and role of non-indigenous museums and contemporary native art. Mary Beth is a member of the IFKN research coordination team.

Mary Beth Jäger (Citizen Potawatomi) is a research analyst for the Native Nations Institute (NNI) at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at the University of Arizona. Mary Beth's work at the UA's NNI expands across a diverse range of indigenous governance areas. Some of those areas include child welfare, tribal justice systems, citizen entrepreneurship and role of non-indigenous museums and contemporary native art. Mary Beth is a member of the IFKN research coordination team.

Lydia Jennings (Pascua Yaqui and Huichol) is a PhD candidate in the Department of Soil, Water, and Environmental Science at the University of Arizona. Her research interests are in soil health, environmental remediation, Indigenous science, mining policy, and environmental data ownership by tribal nations. Lydia is a 2014 University of Arizona NIEHS Superfund Program trainee, a 2015 recipient of National Science Foundation's Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and a 2019 American Geophysical Union "Voices for Science" Fellow.

Lydia Jennings (Pascua Yaqui and Huichol) is a PhD candidate in the Department of Soil, Water, and Environmental Science at the University of Arizona. Her research interests are in soil health, environmental remediation, Indigenous science, mining policy, and environmental data ownership by tribal nations. Lydia is a 2014 University of Arizona NIEHS Superfund Program trainee, a 2015 recipient of National Science Foundation's Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and a 2019 American Geophysical Union "Voices for Science" Fellow.

Amy Juan (Tohono O'odham) is Office Manager for the International Indian Treaty Council, where she works on a variety of files including human rights and border issues. Amy is also the founder of Sovereign Remedies, LLC.

Amy Juan (Tohono O'odham) is Office Manager for the International Indian Treaty Council, where she works on a variety of files including human rights and border issues. Amy is also the founder of Sovereign Remedies, LLC.

Stephanie Russo Carroll (Ahtna Athabascan) is based at the University of Arizona where she is Assistant Professor of Public Health and for the American Indian Studies Graduate Interdisciplinary Program; Assistant Research Professor, Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy; and Associate Director, Native Nations Institute in the Udall Center. Stephanie's research explores the links between governance, data, the environment, and community wellness. She co-founded the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network and the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group at the Research Data Alliance, and is a founding member and chair of the Global Indigenous Data Alliance.

Stephanie Russo Carroll (Ahtna Athabascan) is based at the University of Arizona where she is Assistant Professor of Public Health and for the American Indian Studies Graduate Interdisciplinary Program; Assistant Research Professor, Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy; and Associate Director, Native Nations Institute in the Udall Center. Stephanie's research explores the links between governance, data, the environment, and community wellness. She co-founded the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network and the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group at the Research Data Alliance, and is a founding member and chair of the Global Indigenous Data Alliance.

Dan Ferguson is Director of Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS) program at the University of Arizona. His research focuses on three related areas: methods and processes for building scientist/practitioner partnerships to address climate-related issues in society; climate impacts and adaptation strategies in Indigenous communities; and community climate resilience planning in arid and semi-arid regions.

Dan Ferguson is Director of Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS) program at the University of Arizona. His research focuses on three related areas: methods and processes for building scientist/practitioner partnerships to address climate-related issues in society; climate impacts and adaptation strategies in Indigenous communities; and community climate resilience planning in arid and semi-arid regions.