By: Aron L. Crowell, Alaska Director, Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution

In a recent study, a team of investigators analyzed oxygen-18 isotopes (δ18O) from the otoliths—or ear bones—from archeological Pacific cod (dating about 1790-1920) to reconstruct nearshore temperature regimes in the Gulf of Alaska. By comparing those values to δ18O levels in fish sampled in the same location in 2004, the team determined that ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Alaska today are about 3˚C warmer than they were during the late Little Ice Age (LIA) two centuries ago. The work was supported by NSF, the National Park Service, and the Oceans Alaska Science and Learning Center in Seward, Alaska.

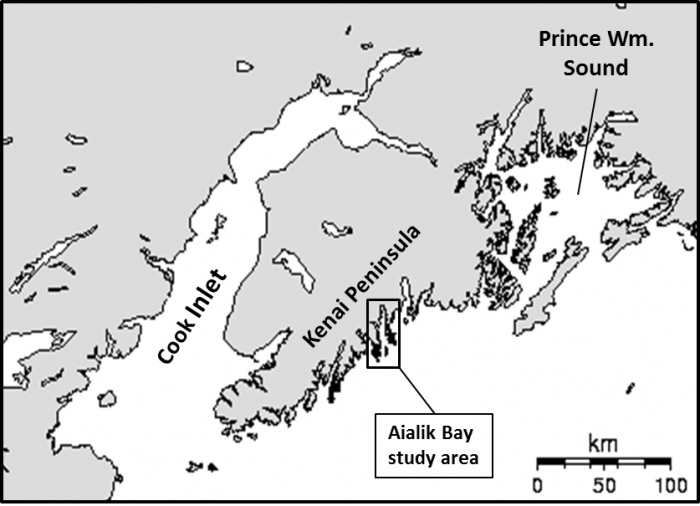

The results, published in the June 2017 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports (Helser et al. In Press) are based on the analysis of Pacific cod otoliths found at two historic Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) maritime village sites in Aialik Bay, on the southeast coast of Alaska's Kenai Peninsula (Figure 1). The samples were collected at the late LIA Early Contact Village site, dated about A.D. 1790-1820, and from the transitional LIA Denton Site, dated about A.D. 1850-1920. Excavations were conducted in 2003-2004 as part of the Kenai Fjords Oral History and Archaeology Project, directed by Aron Crowell and funded by the National Park Service (Figure 2).

Because δ18O levels have an inverse relationship to temperature, those levels sequestered in otoliths can be used as thermal gauges that track warming and cooling in the ocean environment. Higher δ18O levels (indicating colder waters) were found in Pacific cod otoliths from the late LIA Early Contact Village site than those found in samples from the transitional LIA Denton Site, while δ18O levels in fish sampled at Aialik Bay in 2004 were the lowest of all.

Archaeozoological records such as these represent the intersection of human and animal behavior, offering insights into both. For example, sampling of annual growth rings on the Aialik Bay otoliths show that Pacific cod typically move from warm, shallow waters in their first years to deeper, colder waters at maturity. The same life-history curves were seen on all samples, both contemporary and archaeological. All of the archaeological otoliths analyzed in this study were from fish that were five- to six-years old when caught, which indicates that Sugpiaq fisherman were targeting large, fully-grown fish in relatively deep waters. From artifacts and ethnohistorical data, we know the Sugpiaq took these mature cod at depths of 85-120 meters using bottom-fishing rigs made up of a dried kelp line, bone hooks suspended from a wooden spreader, and a grooved anchor stone (Birket-Smith 1941; Holmberg 1985; Korsun 2012; Steffian et al. 2015). The skeletal bones of Pacific cod are more abundant at the Aialik sites than those of any other fish, indicating that this species was highly important in Sugpiaq diets of the late and transitional Little Ice Age.

The environmental and cultural implications of temperature cycles in the Gulf of Alaska are significant. Over time, Pacific cod and salmon have alternated as the most abundant species at Gulf of Alaska archaeological sites but appear to have responded in opposite directions to major temperature shifts, with cod favoring relatively cold waters and salmon increasing during warm phases. For example, Pacific cod predominated at Sanak Island, located near the southern tip of the Alaska Peninsula in the western Gulf of Alaska, during the cold late Neoglacial period. Pacific cod gave way to salmon during the early Medieval Warm Period (A.D. 900-1350), and increased to primacy again during the colder LIA (A.D. 1350-1900) (Maschner et al. 2008). Similar temperature-related transitions occurred on Kodiak Island where extensive Sugpiaq settlement took place along the island's western salmon rivers during the Medieval Warm Period when these fish flourished, which was followed by a shift of the population during the LIA to the eastern side of the island where cod and other offshore resources were more accessible (Clark 1987; Finney et al. 2002; Knecht 1995; West 2012).

The Gulf of Alaska coast of the Kenai Peninsula, discussed here, has similarities to eastern Kodiak Island and may have been a cold-cycle expansion zone for Sugpiaq populations that focused elsewhere on salmon during warmer periods. Plans are under way to expand the otolith study to include a larger sample of Gulf of Alaska sites and to cover a greater time span, potentially 6,000 years or more, in order to examine these broad patterns using new data.

For further information, please contact Aron L. Crowell (crowella [at] si.edu)

For additional information on the Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) people of southern Alaska, please see the Arctic Studies Alaska Native Collections.

More information about the Smithsonian Institution's Arctic Studies Center is available on their website.

Smithsonian Institution's Arctic Studies Center is an ARCUS member institution.

References

Birket-Smith, K., 1941. "Early Collections from the Pacific Eskimo." Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Etnografisk Raekke I-II. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

Clark, D. W., 1987. "On a clear day you can see back to 1805: ethnohistory and historical archaeology on the southeastern side of Kodiak Island, Alaska." Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 21(1-2):105-132.

Finney, B. P., I. Gregory-Evans, M. S. V. Douglas, and J. P. Smol, 2002. "Fisheries productivity in the northeastern Pacific Ocean over the past 2,200 years." Nature 416(18):729-733.

Helser, T., C. Kastelle, A. Crowell, J. Valley, I. Orland, R. Kozdon, and T. Ushikobo, In Press. "A 200-year archaeozoological record of Pacific cod (Gadus Macrocephalus) life history as revealed through ion microprobe oxygen isotope ratios in otoliths." Journal of Archaeological Science Reports. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.06.037 and http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X1730442X.

Heizer, Robert F., 1952. "Notes on Koniag Material Culture." Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 1(1):11-24.

Holmberg, Heinrich J., 1985. "Holmberg's Ethnographic Sketches," ed. M. W. Falk, trans. F. Jaensch. Fairbanks: The University of Alaska Press.

Knecht, R. A., 1995. "The late prehistory of the Alutiiq people: culture change on the Kodiak archipelago from 1200-1750 A.D.", Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Bryn Mawr College, Philadelphia.

Kopperl, R. E., 2003. "Cultural complexity and resource intensification on Kodiak Island, Alaska," Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, Seattle.

Korsun, S. A., 2012. "The Alutiit/Sugpiat: A Catalog of the Collections of the Kunstkamera." Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Maschner, H. D. G., M. W. Betts, K. L. Reedy-Maschner, A. W. Trites, 2008. "A 4500-year time series of Pacific cod (Gadus microcephalus) size and abundance: archaeology, oceanic regime shifts, and sustainable fisheries." Fishery Bulletin 106(4):386-394.

Steffian, A. F., M. A. Leist, S. D. Haakanson, and P. G. Saltonstall (eds), 2015. "Kal'unek From Karluk: Kodiak Alutiiq History and the Archaeology of the Karluk One Village Site." Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

West, C. F., 2015. "Learning from Fish Bones. In Kal'unek From Karluk: Kodiak Alutiiq History and the Archaeology of the Karluk One Village Site,"ed. A. F. Steffian, M. A. Leist, S. D. Haakanson, and P. G. Saltonstall, pp. 156-157. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.