By: Lawrence Hamilton, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire

Jochen Wirsing, Department of Sociology, University of New Hampshire

Jessica Brunacini, Columbia Climate Center, Columbia University

Stephanie Pfirman, Environmental Science, Barnard University; and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University

Arctic warming has raised the visibility of this region for people to the south. As scientists, governments, corporations, and Arctic residents face new challenges, the general public also hears more news about Arctic change. Such news creates public awareness, but communicates just fragmentary knowledge. Although certain memes such as "ice melting" or "possible effects on my weather" become widespread, more basic geographical knowledge does not travel as far. A number of surveys since 2006 have traced the outlines of U.S. public awareness, finding substantial but often politically-linked concerns about polar-region change (Hamilton 2008; Hamilton, Cutler & Schaefer 2012). Two different kinds of "knowledge" stand out in these studies: facts that do or do not link directly to respondents' political identity and what they believe about climate change. Most people are aware of melting sea ice, for example, although this awareness correlates with their political orientation. On the other hand, most cannot guess whether Arctic sea ice or Greenland/Antarctic land ice has the greater potential to raise sea level (Hamilton 2012, 2015).

The Polar, Environment, and Science (POLES) survey, carried out in two stages in August and November–December of 2016, is the most recent nationwide project to assess Arctic knowledge. The two-stage design allowed testing for differences before and after the U.S. election, but those turned out to be minor. Another unique aspect of this survey was its deliberate oversampling of Alaska residents, so for the first time we could compare their Arctic knowledge with that of other U.S. residents. Random-sample telephone interviews were carried out by trained interviewers at the Survey Center of the University of New Hampshire. Of the 1,407 people interviewed, 398 live in Alaska, with the remainder scattered among other states. A published report on the August stage of this survey gives details about survey methods and the full range of questions asked (Hamilton 2016). This article includes the November–December interviews as well, for a sharper view of how Alaska residents compare with other Americans in their knowledge about the Arctic.

Four basic knowledge questions are listed below, with correct answers marked by asterisks; in telephone interviews, the order of response choices was rotated to avoid bias:

Which of the following three statements do you think is more accurate? Over the past few years, the ice on the Arctic Ocean in late summer...

- Covers less area than it did 30 years ago.*

- Declined but then recovered to about the same area it had 30 years ago.

- Covers more area than it did 30 years ago.

Which of the following possible changes would, if it happened, do the most to raise sea levels?

- Melting of sea ice on the Arctic Ocean.

- Melting of land ice in Greenland and the Antarctic.*

- Melting of glaciers in the Himalaya and Alaska.

Which of these statements best describes the North Pole?

- Ice a few feet or yards thick, floating over a deep ocean.*

- Ice more than a mile thick, over land.

- A mainly rocky, mountainous landscape.

Which of the following countries has territory with thousands of people living north of the Arctic Circle?

- United States*

- China

- Estonia

- Great Britain

- none of these

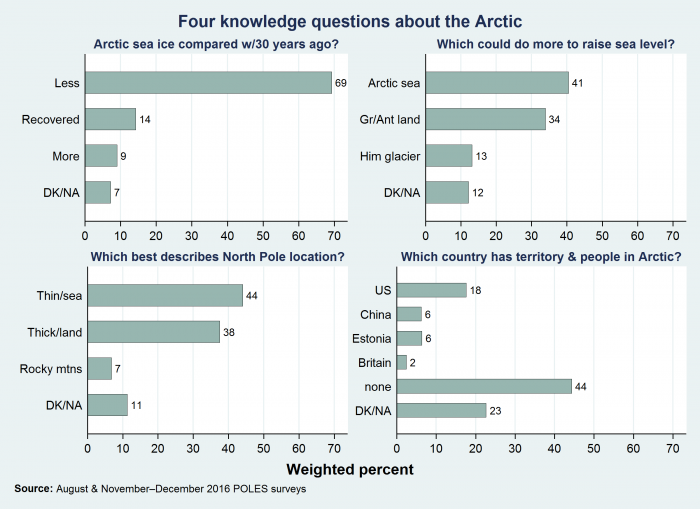

Figure 1 charts the response percentages. Sixty-nine percent accurately say that late-summer Arctic sea ice covers less area than it did 30 years ago. This is the type of question that respondents might guess (right or wrongly) from their general beliefs about climate change. The other three questions are purely geographical, however, and not guessable in this way. Their accuracy rates are much lower. Only 34 percent recognize that the thick Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets could do most to raise sea level (adding more than 200 feet if both melted). On the other hand, the potential contribution from Arctic sea ice, which is already floating, would be negligible. Forty-four percent know that the North Pole is located over a deep ocean, although the Arctic Ocean is prominent on any world map or globe. Finally, just 18 percent know that the U.S. has territory with thousands of people living north of the Arctic Circle. Many respondents thought this last one was a trick question to which we were offering no correct answer.

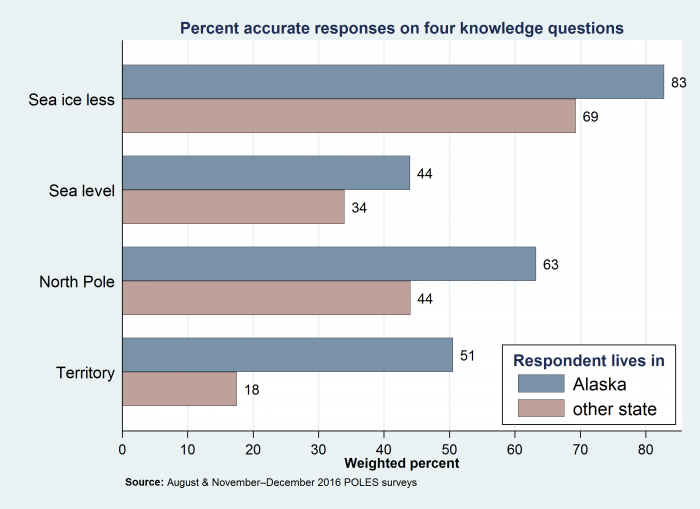

In designing this study, we expected that Alaska residents would prove to be more knowledgeable about the Arctic. Northern Alaska has an Arctic Ocean coastline, icebound for much of the year, and sea ice affects the state's west coast as well. More than a quarter of Alaska's land area lies north of the Arctic Circle, a region including the towns of Barrow (2015 population 4,554) and Kotzebue (3,267), along with many smaller villages. Figure 2 charts percentages of accurate responses from Alaska residents, compared with those from all other U.S. states.

On each of these questions, Alaskans are significantly more likely than other Americans to answer correctly. That said, the Alaskans also display limited knowledge, reflecting the fact that most live in more southerly, non-Arctic parts of the state. Although eighty-three percent correctly say that Arctic sea ice has declined, less than half know that land ice rather than sea ice affects sea level, and just 63 percent know the location of the North Pole. Most striking, only half of the Alaska respondents realize the U.S. has territory and population in the Arctic, although such territory and population is entirely within their own state.

Previous surveys have found that political outlook and beliefs about climate change lead some people to reject scientific facts on this topic. For example, people who disbelieve the scientific consensus that humans are changing Earth's climate also are less likely to acknowledge the well-established fact that Arctic sea ice has declined in the past 30 years (Hamilton 2012). This pattern occurs in the recent POLES surveys as well. However, the other Arctic knowledge questions do not link so obviously to climate-change beliefs. The high rates of wrong answers on these items indicate a lack of basic information. It does not result just from people being far from the Arctic; even those living in the same state often get these questions wrong. These results emphasize the need for more effective communication of scientific, geographic, and social information about the Arctic.

More information about the PoLAR Partnership is available on their website.

Acknowledgments

Support for the POLES surveys was provided by the PoLAR Partnership grant from the National Science Foundation (DUE-1239783), with additional help from the New Hampshire EPSCoR Safe Beaches and Shellfish project (IIA-1330641). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

References

Hamilton, L.C. 2008. "Who cares about polar regions? Results from a survey of U.S. public opinion." Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 40(4):671–678.

Hamilton, L.C. 2012. "Did the Arctic ice recover? Demographics of true and false climate facts." Weather, Climate, and Society 4(4):236–249. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-12-00008.1

Hamilton, L.C., M.J. Cutler & A. Schaefer. 2012. "Public knowledge and concern about polar-region warming." Polar Geography 35(2):155–168. doi: 10.1080/1088937X.2012.684155

Hamilton, L.C. 2015. "Polar facts in the age of polarization." Polar Geography 38(2):89–106. doi: 10.1080/1088937X.2015.1051158

Hamilton, L.C. 2016. "Where is the North Pole? An election-year survey on global change." Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/285/