By: Harry Stern, Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington

A new exhibit at the Anchorage Museum, entitled "Arctic Ambitions," examines the log of Captain James Cook, the preeminent navigator of his age, as he sailed north through Bering Strait into the Arctic Ocean in search of the Northwest Passage. The exhibit considers whether Cook would have discovered the passage if sea-ice conditions in 1778 were similar to those of today.

At daybreak on 7 March 1778, "the long looked for Coast of new Albion was seen"1 by Captain James Cook from the deck of the HMS Resolution. He had come with two ships and 150 men to the northwest coast of North America in search of a Northwest Passage to the Atlantic Ocean. For the next five months he sailed along the coast of present-day British Columbia and Alaska, exploring promising inlets and encountering numerous indigenous peoples.

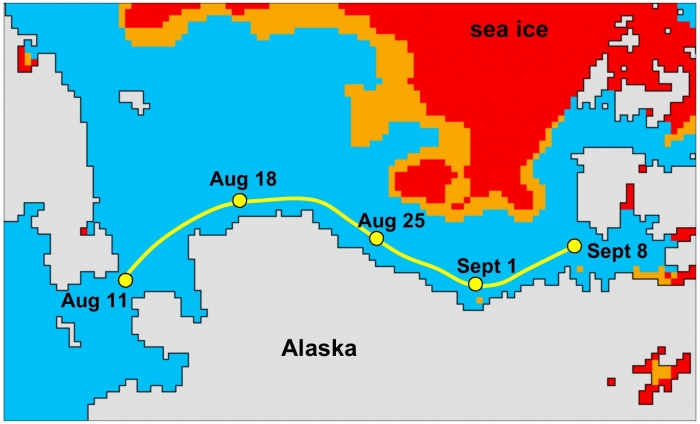

On 11 August, Cook sailed north through the Bering Strait into the Arctic Ocean. Working his way along the coast of Alaska, his progress was halted a week later by "ice which was as compact as a Wall and seemed to be ten or twelve feet high at least." This marked the farthest north reach of Cook's voyage at 70°44′ N latitude, just west of present-day Wainwright, Alaska. Retreating southward six leagues (about 18 miles), he encountered "a point which was much incumbered with ice for which Reason it obtained the name of Icey Cape" (see Figure 1). According to Beaglehole2 this is 18 August 1778, off Icy Cape, when Cook wrote, "Our situation was now more and more critical, we were in shoald water upon a lee shore and the main body of the ice in sight to windward driving down upon us. It was evident, if we remained much longer between it and the land it would force us ashore." He turned westward, and for the next 11 days sailed close to the ice edge, trying to find an opening to the north. On 29 August having reached the coast of Siberia at 69° N without finding a break in the ice, he abandoned the search, since "so little was the prospect of succeeding." He sailed south through the Bering Strait on 2 September.

Captain Cook is justly famous for his exploration of the South Pacific, but his contributions to the exploration of the North Pacific and the Arctic are arguably equally significant. The exhibit at the Anchorage Museum, Arctic Ambitions: Captain Cook and the Northwest Passage, examines the legacy of this northern voyage with artifacts, art, and hands-on activities. The exhibit runs through 7 September 2015, and will open at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma on 16 October 2015. Accompanying the exhibit is a book also titled Arctic Ambitions—a collection of essays that shed new light on Cook's northern exploration. The paragraph above is taken from one of the essays, 'Sea Ice in the Western Portal of the Northwest Passage from 1778 to the 21st Century,' in which the author examines historical and modern sea-ice conditions in the region north of the Bering Strait, and asks whether Cook would have discovered the Northwest Passage in 1778 if sea-ice conditions had been as they are today. The answer is suggested in Figure 2, which shows Cook's hypothetical progress in today's Arctic Ocean. By 18 August the sea-ice has typically retreated hundreds of kilometers offshore, opening up a navigable coastal route. Cook would have had time to reach Amundsen Gulf and know that he had discovered a promising passage before returning to the Bering Strait ahead of fall freeze-up.

Other essays in Arctic Ambitions give the historical context of Cook's voyage; describe his encounters with the indigenous people; and demonstrate that the Arctic is once again a region of strategic significance, where issues of navigability, national sovereignty, and resource extraction are occupying the attention of world powers, just as in Cook's day.

More information is available on the Anchorage Museum website.

Acknowledgements

Stern thanks David Nicandri and Julie Decker for their contributions to this article.

Reference notes

-

Quotations are from The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, vol. 3, The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery, 1776–1780, ed. J. C. Beaglehole (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1967). ↩︎

-

Arctic Ambitions: Captain Cook and the Northwest Passage, edited by James K. Barnett and David L. Nicandri, preface by Robin Inglis, published March 2015, 448 pages with 187 color illustrations, University of Washington Press. See http://www.washington.edu/uwpress/search/books/BARCOO.html ↩︎