By: Olga Ulturgasheva, Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge and Stacy M. Rasmus, Center for Alaska Native Health Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The international and multidisciplinary project "Negotiating Pathways to Adulthood" explored the indigenous adolescent experience at the critical time of transition from adolescence to young adulthood among Alaskan Yup'ik, Alaskan Inupiat, Canadian Inuit, Norwegian Sami, and Siberian Eveny. Funded by NSF, this collaborative and multi-sited study examined the challenges these adolescents face and the resources and strategies they use to cope with hardship and adversity. The project developed insights into the family, community, and cultural contexts that support healthy youth and identified key protective factors that may promote development of effective culturally compatible prevention programs. Such prevention programs aim to reduce current disproportionately high rates of substance abuse and suicide, build indigenous research capacity, and develop a collaborative network of researchers and community members.

The research process involved engaging, interviewing, and observing 100 indigenous young people across gender and across two age groups signifying early (11-14 years old) and late (15-18 years old) adolescence. The data from five communities was collected and analyzed by researchers at Siberian Eveny, Alaskan Yup'ik, and Norwegian Sami sites, and supplied by community collaborators and later processed by researchers at the Alaskan Inupiat and Canadian Inuit sites. The study highlights the need for social policy to be based on long-term ethnographic research and analysis at the community and family level. Conducting research in the community, participating in people's—especially young people—lives, speaking to them in person, and observing them in action, are pivotal to doing useful and effective community research in the Arctic.

The research findings point at assemblages of shared experiences among arctic youth in their transition to adulthood: common patterns in the spheres of schooling, subsistence practices, Indigenous identity construction, inter- and intra-generational relations, and violence and emotional hardship related to bullying and boredom. Project data show that the youth resilience strategies are shaped by and are an outcome of communal effort (i.e., family, kin, or peer-support). More specifically, researchers found that while facing situations of hardship and adversity, youth from each community deploy socially important and locally accessible resources such as local networks of sharing, extended and fluid households, grandparents and other important care-takers, kin/peer support, and subsistence activities (e.g., reindeer herding, hunting, and fishing) as strategies for being well and strong. Some of these resources cited by the youth—such as parents, school, and subsistence activities—at times also presented special challenges. This points to a complex model of negotiation enacted by youth as they determine how to live in their communities—using strategies that build in the necessary flexibility to maximize available, while not always reliable, local resources. Arctic indigenous youth still deploy culturally integrated mechanisms of protection but give them fresh meanings as they put them to use in new situations and towards new ends.

Preliminary findings were shared and discussed by indigenous youth, community members, and university researchers at the international Circumpolar Indigenous Pathways to Adulthood (CIPA) study workshop at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. in October 2012 (see Figure 1). Prior to the workshop, two of the indigenous researchers on the circumpolar team (Ulturgasheva and Rasmus) had involved youth in the production of a digital community portrait and an auto-ethnographic video film, "One Day From My Life," which then were screened during the workshop. Digital presentations of the research findings provided contextual framework for understanding socialization patterns and resilience-shaping processes in the communities. The presentations also stimulated comparative discussion among the workshop participants from all sites.

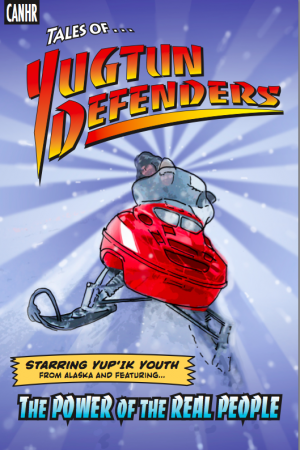

Outcomes from this research include the development of innovative, indigenous, youth-centred research methodologies. These resulted in production of material that can be digitally disseminated for youth on the move in the Eveny reindeer herding communities and in the production of a comic book-themed research report for Yup'ik Alaska Native youth (see Figure 2). This project also contributed to transformative outcomes for the indigenous youth and for the university researchers involved in the participatory and co-learning research process. Most significantly, indigenous youth involved in the cross-site workshop left feeling stronger, more connected, and more confident and hopeful in their futures. One of the outcomes is collaboration between indigenous researchers from Alaska and Siberia. Rasmus and Ulturgasheva have recently launched a new study that examines the practice of indigenous researchers working with indigenous communities, both their own and others, and provides a critical new take on the traditional insider-outsider dilemma in social science research.

Rasmus and Ulturgasheva have continued to build relationships between Siberian Eveny and Alaskan Yup'ik with the goal of increasing local resources networks through the creation of an international arctic context for resilience.

For further information, please contact Olga Ulturgasheva (ou202 [at] hermes.cam.ac.uk) and Stacy Rasmus (smrasmus [at] alaska.edu).

The projects featured in this article are supported by funding from the National Science Foundation.