The Bering Sea Project is a multiagency integrated ecosystem study of the eastern Bering Sea. This six-year project received over $50 million from a 2007 NSF and North Pacific Research Board (NPRB) partnership plus significant contributions from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and the National Marine Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center. It has supported 43 collaborative research projects, nearly 100 principal investigators, plus postdoctoral scholars, graduate students, and technicians. With assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies, the Bering Sea Project assembled monetary and ship resources that would have been beyond the reach of any one agency. Now in the synthesis and writing phase, the Bering Sea Project promises to deliver a wealth of new knowledge and understanding of the mechanisms controlling the flow of energy and material through Bering Sea pelagic and benthic food webs, and an enhanced ability to anticipate the inevitable changes that will occur with global warming.

A Brief History of Eastern Bering Sea Oceanographic Programs

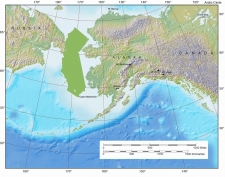

A large marine ecosystem requires a major scientific effort to investigate in its entirety. The eastern Bering Sea shelf is over 1,200 kilometers in length and 500 kilometers in width, constitutes about 50% of the Bering Sea extent of 2,304,000 square kilometers. Despite being the source of some of the largest and most lucrative fisheries in the United States, the eastern Bering Sea received surprisingly little oceanographic study prior to the Bering Sea Project, relative to its size and economic importance (see inset below right).

After the conclusion of the Inner Shelf Transfer and Recycling (ISHTAR) program, most eastern Bering Sea programs were relatively small, resource-limited, and focused at a regional level within the eastern Bering Sea. However, these programs were important precursors to the current Bering Sea Project because they were interdisciplinary in nature and involved collaborations among NOAA scientists and academics, and in many cases involved significant sharing of resources.

Recent NOAA Programs Have Contributed to the Knowledge Base

- The North Pacific Climate Regimes and Productivity (NPCREP) has collaborated with the Bering Sea Project by providing important data from times of the year and areas not covered in the other studies.

- The United States portion of the [North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission’s Bering-Aleutian Salmon International Survey (BASIS), begun in 2000, has evolved into an ongoing component of NOAA’s management tools for the Bering Sea.

- The Alaska Fishery Science Center has continued and expanded the BASIS survey over the eastern Bering Sea shelf, providing coverage of the shelf ecosystems in late summer and early fall—times not otherwise sampled in the Bering Sea Project.

- BASIS and the Pribilof Islands Project provided important oceanographic sampling during the warm years of 2000–2005.

The Seed for NSF’s Bering Sea Ecosystem Study (BEST) Science Plan

In early 2002, Hunt and others submitted to NSF a draft manuscript that described the possibilities of a large-scale oceanographic program focused on the potential impacts of climate change on the eastern Bering Sea ecosystem. Neil Swanberg, NSF Arctic Natural Sciences Program Manager at that time, subsequently funded an international planning workshop to review available data and provide advice as to the feasibility and value of proceeding with a large interdisciplinary study of the Bering Sea (see Ecosystem Studies of Sub-Arctic Seas: Results of a Workshop held in Laguna Beach, California, 6 September 2002). Workshop participants included oceanographers working in the North Atlantic Ocean, the western North Pacific Ocean, and the Bering Sea. Both Neil Swanberg and Clarence Pautzke, the newly appointed Executive Director of the North Pacific Research Board (NPRB), attended the workshop and identified the potential value of collaboration between NSF and NPRB in developing an integrated ecosystem studies in the Bering Sea. In March 2003 a second planning workshop convened in Seattle, Washington resulting in the development of the 2004 Bering Ecosystem Study (BEST) Science Plan. NSF launched the first BEST field season in spring of 2007.

Summary of Eastern Bering Sea Oceanographic Programs

Mid-1970s to the Mid-1980s

Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land management (BLM) (now BOMRE), in collaboration with NOAA, conducted a $100 million study of the Bering Sea region called the Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program (OCSEAP): This study provided baseline information on the Bering Sea environment in support of lease sales for hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation on the outer continental shelf of the eastern Bering Sea. Many issues were explored, from contaminant analyses to social and economic studies, with oceanographic studies focused primarily on investigating the ecosystems of potential lease areas and developing a broad suite of studies of the life histories, food habits, abundances, and distributions of the key species or groups that were of ecosystem or economic importance.

1974–1982 (Overlapping OCSEAP)

NSF-funded Processes and Resources of the Eastern Bering Sea Shelf (PROBES): This program focused primarily on examining variability, from physics to seabirds, across the southeastern Bering Sea shelf from Cape Newenham to the shelf edge. PROBES was a process-oriented program, but despite overlap between the principal investigators participating in PROBES and OCSEAP, there was little joint planning, division of effort, or sharing of resources between the two programs.

1983–1989

Inner Shelf Transfer and Recycling (ISHTAR): This project was a multiyear interdisciplinary program that focused on the sources of nutrients that supported the high rates of production in the northern Bering and Chukchi Seas.

1991–1997

NOAA-funded program Bering Sea Fisheries Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (BS FOCI).

1997–2001

Inner Front Project, which overlapped and built on work from BS FOCI. These two programs collaborated in producing a series of papers in 2001 documenting the unusual conditions encountered in 1997 and two special volumes that focused mainly on the eastern Bering Sea.

Contributions of Recent NOAA Programs

- The North Pacific Climate Regimes and Productivity (NPCREP) program has collaborated with the Bering Sea Project by providing important data from times of the year and areas not covered in the other studies.

- The U.S. portion of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission’s Bering-Aleutian Salmon International Survey (BASIS), begun in 2000, has evolved into an ongoing component of NOAA’s management tools for the Bering Sea.

- The Alaska Fishery Science Center has continued and expanded the BASIS survey over the eastern Bering Sea shelf providing coverage of the shelf ecosystems in late summer and early fall, times not otherwise sampled in the Bering Sea Project.

- BASIS and the Pribilof Islands Project provided important oceanographic sampling during the warm years of 2000–2005.

NPRB Develops a Science Plan

Contemporaneous with development of the BEST Science Plan a long-term science plan for NPRB was drafted. The draft, written largely by Jim Schumacher, received guidance from a National Research Council panel tasked with developing a plan for guiding the NPRB funding program. The resulting NPRB Science Plan emphasized the importance of large-scale integrated studies of the marine ecosystems of the eastern North Pacific, similar to that being developed by BEST for the Bering Sea. NPRB launched its first Integrated Ecosystem Research Program in the Bering Sea in 2008. The question was: could the two agencies with very different cultures and goals collaborate or would they compete for ship time and scientific manpower? There was much good will and talk of cooperation, but there were also institutional stumbling blocks.

Collaboration Begins

The first opportunity for collaboration came in the early spring of 2007 when NSF announced funding for the first round of the BEST funding competition. The initial cohort did not include programs for conducting the basic hydrographic, chemical, and plankton measures, nor a primary production component. The BEST Science Steering Committee and NOAA scientists active in the southeastern Bering Sea expressed concern about these missing elements and offered a solution. A group of NOAA scientists would forego their planned and funded spring 2007 cruise and join the BEST scientists on the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy. Their work would ensure a full suite of oceanographic measurements to complement those being funded by NSF. The sticking point was that NSF initially wanted the NOAA scientists on the Healy to sail on a “not to interfere” basis, giving them little or no say in the planning or execution of the cruise. After high-level interagency negotiations an agreement was reached: the Chief Scientist would be an NSF-sponsored scientist, otherwise all Principal Investigators on board were on an equal footing. Excellent collaboration was achieved and the beginnings of a broadly collaborative effort were underway.

Both NSF and NPRB planned to issue calls for proposals for fieldwork commencing in 2008. Clarence Pautzke, Executive Director of NPRB, and Bill Wiseman, the current Arctic Natural Sciences Program Manager at NSF, engaged in a series of negotiations that resulted in an historic partnership for work in the Bering Sea. The agreement was to partition the work with NSF funding climate, ocean physics, and lower trophic-level through zooplankton studies, and the NPRB funding studies of large zooplankton through fish, seabirds, and fisheries. The agreement included a major commitment to modeling in this joint program. To ensure that the programs would mesh well, there was also a precedent-breaking agreement that there would be representatives of each of the funding communities on both the NSF and the NPRB proposal review panels. Although NSF elected to fund a series of individual proposals and NPRB selected to seek fully integrated large proposals, there were strong mechanisms in place to ensure that the work funded by NSF and NPRB would be well integrated.

NOAA Joins the Program

NOAA scientists interested in Bering Sea also threw their full weight behind the new integrated Bering Sea program, seeing immediately its potential value for enhancing understanding of the mechanisms affecting fish stocks in the Bering Sea. With the strong support of Doug DeMaster, Director of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA scheduled extra surveys in the Bering Sea and supported geographic enlargement of planned surveys, thereby complementing the work funded by NSF and NPRB. The result was the support of scientific cruises to the Bering Sea from early spring—when moorings were put out by NOAA scientists accompanied by others taking hydrographic, chemical, and biological samples—to major broad-scale sampling of the eastern shelf in late August and September.

These combined NSF, NPRB, and NOAA efforts provide the first shelf-wide scientific coverage of the eastern Bering Sea and the first nearly continuous seasonal coverage from early March through to mid-September. The stage was set to gather an unprecedented quantity of data and to do it in a fashion that supported the development of comprehensive climate-to-fish and fisheries models that would provide an integration of the immense and complicated dataset to be gathered. The Bering Sea Project, as it has become known, had a Science Advisory Committee with representation of all parts of the project. The Bering Sea Project also had an Ecosystem Modeling Committee, funded by NPRB, that consisted of scientists who were not funded in the program who were charged with overseeing the development of the modeling program and providing advice to the funding agencies to help the modelers obtain the resources that they needed, both in terms of the equipment and the data necessary to run the models.

The First Results Emerge

Although the Bering Sea Project is just now in its final phase of writing up results and synthesizing the multiple lines of evidence about how climate influences the eastern Bering Sea marine ecosystem, some exciting highlights are already emerging. These include, but are not limited to:

- A new ability to downscale from global climate models to the Bering Sea region, thus allowing modelers to use the predictions of global modals to predict the range of future conditions to be anticipated in the Bering Sea.

- A new appreciation of wind-driven water movement on the eastern Bering Sea shelf and how they can lead to either upwelling or down-welling in the Inner Shelf Domain.

- A new appreciation of the along-shelf heterogeneity of the hydrography, and how the hydrography north of about 60°N differs from that in the southeastern Bering Sea.

- A greatly enhanced understanding of the relative importance of advection and re-mineralization in the nutrient supply of both the northern and southern regions of the shelf.

- A new understanding of the role of sea ice and its associated ice algae in the support of zooplankton in the southeastern Bering Sea.

- A new appreciation for the major role played by micro-zooplankton in the food web and the sensitivity of these organisms to ambient temperatures.

- A new focus on conditions in summer and fall and the importance of on-going primary production and zooplankton for the overwinter survival of walleye pollock.

- A new understanding of the relative importance of top-down and bottom-up processes in the structuring of the eastern Bering Sea food web.

- Exciting new studies that show where marine birds and fur seals from the Pribilof Islands and Bogoslof Island forage and the types of prey aggregations that are of value to them.

- The development and use of a complex set of fully coupled models from climate to physics, nutrients, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fish, fisheries, and communities that will allow development of scenarios of what we may expect in the Bering Sea and its fisheries-dependent communities in the face of climate change.

These results, and those to come, will change our view of the Bering Sea and the factors that are most important for its continued role in supporting the Nation’s most productive fisheries. The new results are already having an impact on the management of the Bering Sea ecosystem and will become increasingly valuable as we move into the uncharted waters of a warming Bering Sea. The managers who had the vision to embrace a big-picture approach to ecosystem science and found the resources to support it, and the cadre of marine scientists and social scientists who conducted the field research, have created a treasure trove of new knowledge and have paved the way for truly collaborative, interdisciplinary science supported by multiple agencies with very differing agendas and cultures. Neither the quantity nor the quality of the science accomplished in the Bering Sea Project would have been possible without the level of cooperation that was achieved.

For further information, please contact: George L. Hunt, Jr. School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (glhunt [at] uci.edu)